Kars, the frontier city that lies on the closed border between Armenia and Turkey, the setting of Orhan Pamuk’s book Snow, is forbidden territory for Fulbright Scholars to Armenia. Our security briefing made it clear that the only open border was with Georgia to the north. While there are tours that could take me from Yerevan, up to Georgia and then to across the Turkish/Georgian border and through Kars, to see the ruins of Ani, the ancient capital of Armenia, I won’t be going there this year. Good thing I had been once before.

the ancient capital of Armenia, I won’t be going there this year. Good thing I had been once before.

In the summer of 1984, with American passports and occult last names—thanks to the conventions of marriage—I had gone to Kars with Peter, to gain access to Ani. The red stone ruins rising above golden fields and the gun towers live on inside me. (Photography was prohibited at that time.) As a young American couple who spoke some Turkish, with a carton of Marlboros for the access bribe, we kept my Armenian ancestry a secret. Secrecy was an especially good thing that summer. Every time we saw a newspaper, it had an anti-Armenian cover story. Threats to the Turkish Olympic team by an Armenian radical group demanding recognition for the genocide caused the team to withdraw from the Los Angeles Olympics.

During that trip, my identity,  like that of the ancient Armenian structures scattered across the landscape, stayed hidden. Official signs for tourists with stark labels like “church” or “fort” concealed the historical presence of Armenians on this land. Armenian lettering carved into the stone of the church in places such as Akhtamar Island in the middle of Lake Van, or defaced but lettered frescoes on others, and the characteristic architecture spoke the truth.

like that of the ancient Armenian structures scattered across the landscape, stayed hidden. Official signs for tourists with stark labels like “church” or “fort” concealed the historical presence of Armenians on this land. Armenian lettering carved into the stone of the church in places such as Akhtamar Island in the middle of Lake Van, or defaced but lettered frescoes on others, and the characteristic architecture spoke the truth.

I shared the truth of my pedigree, in a tea shop in Kars, three weeks into this trip. A young man in the shop started saying things, in Turkish, that made it clear to me that he was Armenian. He nodded with excitement when I explained that my mother was Armenian and my father American, borrowed my Turkish English dictionary, and paged through it till he found the world “mongrel” and showed it to me with a huge welcoming smile.

I shared the truth of my pedigree, in a tea shop in Kars, three weeks into this trip. A young man in the shop started saying things, in Turkish, that made it clear to me that he was Armenian. He nodded with excitement when I explained that my mother was Armenian and my father American, borrowed my Turkish English dictionary, and paged through it till he found the world “mongrel” and showed it to me with a huge welcoming smile.

My mongrel status had always challenged me. With fair skin, auburn hair and freckles, I don’t look as Armenian as my brother and sister. In college, during meetings of the Armenian club at Columbia University, I was an outsider for two reasons: my mongrel status and my politics. I advocated for the importance of recognizing other genocides, such as Cambodia’s Killing Fields, so fresh and raw in the early 1980s. As an outsider, I wasn’t the right material for an Armenian marriage. So like my mother before me I married an odar, a foreigner, a non Armenian, a wonderful man, and there we were in a tea shop in Kars.

Here in Yerevan, nearly thirty years later, whenever people are pleased with some aspect of who I am, they refer to “genetic memory,” as though I have a series of latent codons, that can be expressed only in this environment. Genetic memory lets me learn dance steps. Genetic memory accounts for my spiritual bent. Genetic memory helps me with the language even though we spoke English only at home when I was young. This is a culture where blood counts, where ancestry counts.*

Here in Yerevan, nearly thirty years later, whenever people are pleased with some aspect of who I am, they refer to “genetic memory,” as though I have a series of latent codons, that can be expressed only in this environment. Genetic memory lets me learn dance steps. Genetic memory accounts for my spiritual bent. Genetic memory helps me with the language even though we spoke English only at home when I was young. This is a culture where blood counts, where ancestry counts.*

My Armenian mother, a biology teacher, sometimes patted me on the head saying I had hybrid vigor. But here in the Old Country, I see that the true strength of my mongrel nature is not biological. As a half-breed, I was as affected by the U.S. Civil Rights movement as I was by the fragments of genocide survival stories that I inherited. Together they make me look for the common humanity at the same time as I look for an accurate recognition of history. They make the acts of governments and the acts of individuals distinct. They make me see truth as the road to peace.

A few weeks ago, I met an anthropologist from Turkey, Zeynep Sariaslan, at an interdisciplinary conference here in Yerevan called, SoUS Strategies of (Un)Silencing. She was here to present her ethnographic work on constructing national and ethnic identity in the Kars borderland as part of a broad conversation on how to move beyond the dominant narratives that perpetuate and sustain “oppositional paradigms, (i.e. us/them, inside/outside…)”. Sariaslan used Pamuk’s book Snow as the point of entry into conversations with the residents of Kars. The conference keynote was delivered by renowned writer and accidental anthropologist Amitav Ghosh who spoke about two forgotten Bengali texts in which Indian WWI Prisoners of War bore witness to the genocide. Ghosh showed how these prisoners moved beyond oppositions and crossed borders, both geographical and ideological, to find the common humanity.

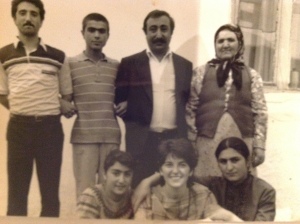

I told Zeynep about my encounter in the tea shop, about hearing of this young man’s time in prison, how the tiny Armenian community managed to find other Armenians to marry, of meeting his family at their home with a massive carpet loom along one wall on which his sisters worked. With this photograph of me with the young man, and his family in 1984, Zeynep offered to help me try to track them down. Crossing ideological borders, finding a common language to speak honestly about the past, ultimately allows for the physical borders to be crossed. This is a good role for a mongrel like me.

shop, about hearing of this young man’s time in prison, how the tiny Armenian community managed to find other Armenians to marry, of meeting his family at their home with a massive carpet loom along one wall on which his sisters worked. With this photograph of me with the young man, and his family in 1984, Zeynep offered to help me try to track them down. Crossing ideological borders, finding a common language to speak honestly about the past, ultimately allows for the physical borders to be crossed. This is a good role for a mongrel like me.

* Perhaps the Armenian emphasis on ancestry accounts for my own fascination with genetics, a fascination which led me to make “Activity Dependent Gene” shown here at Studio Place Arts.

So good to read this, Dana. Such important posts!

Many thanks, Sarah! So much to think about… So good to hear your voice!

Dana, I sent the link to this amazing post to my classmate Maureen Freely, whose book “Enlightment” you may know. xox trina

http://www.guardian.co.uk/profile/maureenfreely

Thank you for sending this on to Maureen Freely, Trina! I will defintiely find her book Enlightenment. I have loved what I have read of Elif Shafak’s books and her review of her latest is compelling. So pleased to share with you the news as well that my verse novel, Stone Pillow, set during the Armenian genocide, was just acquired at auction by Random House/Delacorte.

Simply beautiful …

And if we dig far enough back, aren’t we all mongrel?

So true, Vahan! This is the most wonderful truth of the story of human evolution.

Dana, This is beautifully written. I too grew up with the idea of genetic memory buried in my own hybrid vigor. The road to peace is truth and embracing our full humanity where everyone counts and matters. And oh what riches we will find there if we but allow it. Well said. Thank you. Beebe

And thank you, Beebe, fellow anthropologist and vigorous hybrid! That full humanity is what drew us both to anthropology!

Dana, you are simply an extraordinary person. I am lucky to know you.

Thank you, dear Leda! And I am as lucky to know you!

Pingback: Dana Walrath: Making Art And Writing Stories About The Home of Her Ancestors « MAGIC MIRROR

Thank you for the lovely pieces, Katia.

Dana, this is a beautiful post. I suppose that we as humans all have a genetic memory that informs our identity and now as we become privy to our genetic futures, we are challenged to make sense of its role in our understanding of the self as well. Perhaps truth is the path to peace in this realm too, and to the recognition that in our hopes for the future there too lies a common humanity. Miss you, Nathalie

Thank you, Nathalie! So true! If we go back in time far enough, we are all connected as family, but thousands, hundreds of thousands, and millions are so hard to sense and feel. Sometimes I think that a requirement for any sort of position of political leadership should be an ability to sense the deep past and the distant future where all that we share prevails.

I agree! That would be the true path to peace…